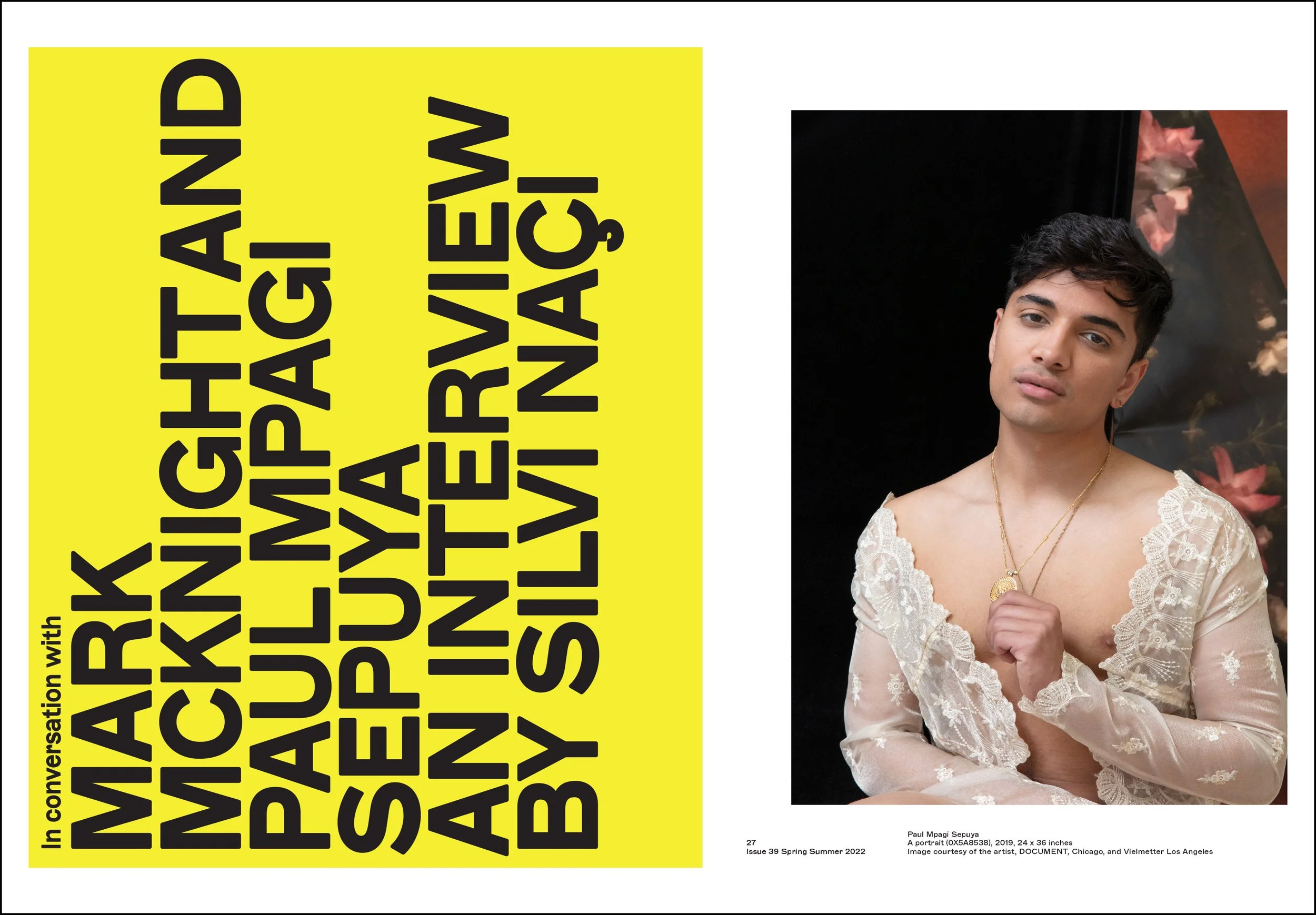

Hunter Fashion Magazine: Mark McKnight & Paul Sepuya

SILVI NAÇI: Thank you both for being open to having this dialogue. I am so excited to have your work in conversation and would love to start with you both describing each other’s work in one sentence.

PAUL MPAGI SEPUYA: Oh I just love Mark’s works, you have to see the prints in person. What to say in one sentence — or maybe one word? Sensual. Reaching.

MARK MCKNIGHT: Paul and his work: generous and generative!

SN: What are some approaches and frameworks you use when starting a new body of work? And how do you see one others work in relationship to yours — through performative gestures, the role they play in forming new identities?

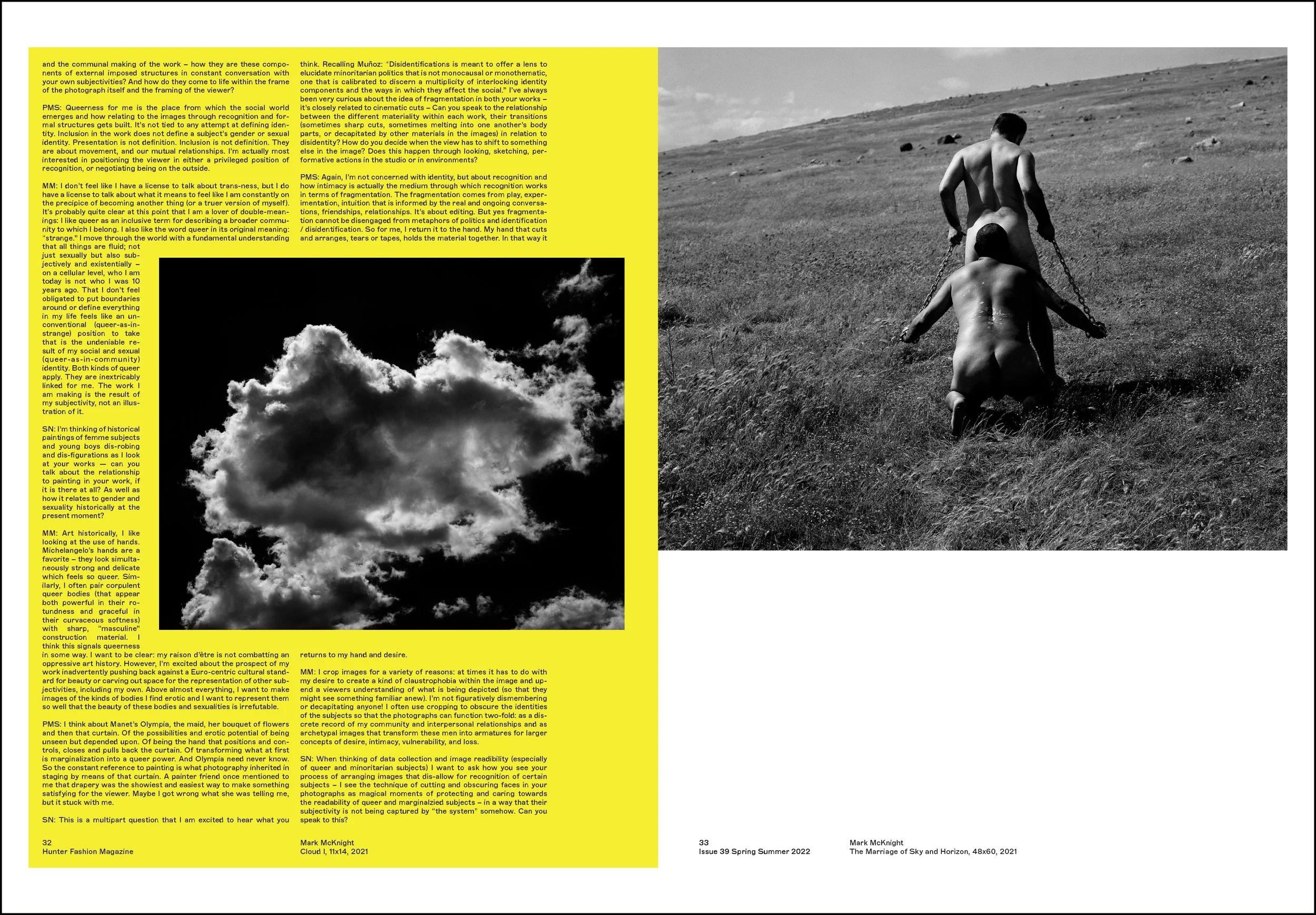

MM: I have always sort of hated that photographers are expected to work in “projects”! I’m an artist, I’m always making or thinking, and after a certain amount of doing those things, I organize a selection of pictures for an exhibition that speaks to a fragment of my experience and/or internal dialog. A photograph that exists in an exhibition that centers on intimacy might fit just as comfortably in a sequence of pictures that foregrounds my interest in entropy – which of course sounds a little absurd — but I think this is the nature of my work: drawing poetic, formal, and figurative parallels between a multitude of subjects so that they can transcend some of these distinctions and exist equivocally. If I’m struggling to get inspired, I load film and go outside or call a friend and ask to make some pictures. One thing about my practice that is both a blessing and a curse is that it’s shot outdoors. I’m bound by time, light, the elements. There is a chance-ness to the process that is really exciting (for example, my fear of getting arrested for making nudes in the LA river or the quality of light changing.) My lack of control allows for improvisation and subsequently a heightened sense of awareness that lends something to the pictures.

PMS: Every work begins in the gaps of what’s still in process, or questions from things that I have recently put out into the world. There is no clear line of new bodies of work. Only ongoing process, like Mark describes, where discrete “projects” are not considered in favor of conversations around exhibitions.There is a lot of boredom, observation and revisiting, all necessary in the studio. There is chance and play that inviting friends into the studio generates. There is failure, there are many outtakes that have sparks of something that may work later on so I have to shoot again. One thing I always have is a set of parameters and limits: the elements involved in the making of the image. The absence of studio lighting and manipulation. The references to prior work. These allow me to go more in depth by not beginning every picture or shoot from scratch.

SN : I am thinking of the relationship between the fetish and voyeurism when making work about portraiture and the body – can you speak to this liminal space between the fetish and voyeurism?

MM: This question brought to mind a 1950 film by Jean Genet (Un Chant d’Amour) that was a really important discovery for me many years ago.. in the film, two prisoners in separate cells are able to see each other through a tiny fissure in the wall that divides them. The closest they ever get to physical intimacy is through this beautifully tragic ephemeral passage of smoke through prison concrete. The wall that divides becomes the unexpected conduit for their unrequited desire… or possibly an instrument in it… which is of course so much more powerful than seeing them fulfill that desire… they are just ecstatically rubbing their bodies against prison concrete before they are eventually interrupted by a guard-cum-voyeur who also plays a role in the surreal exchange.

I digress…

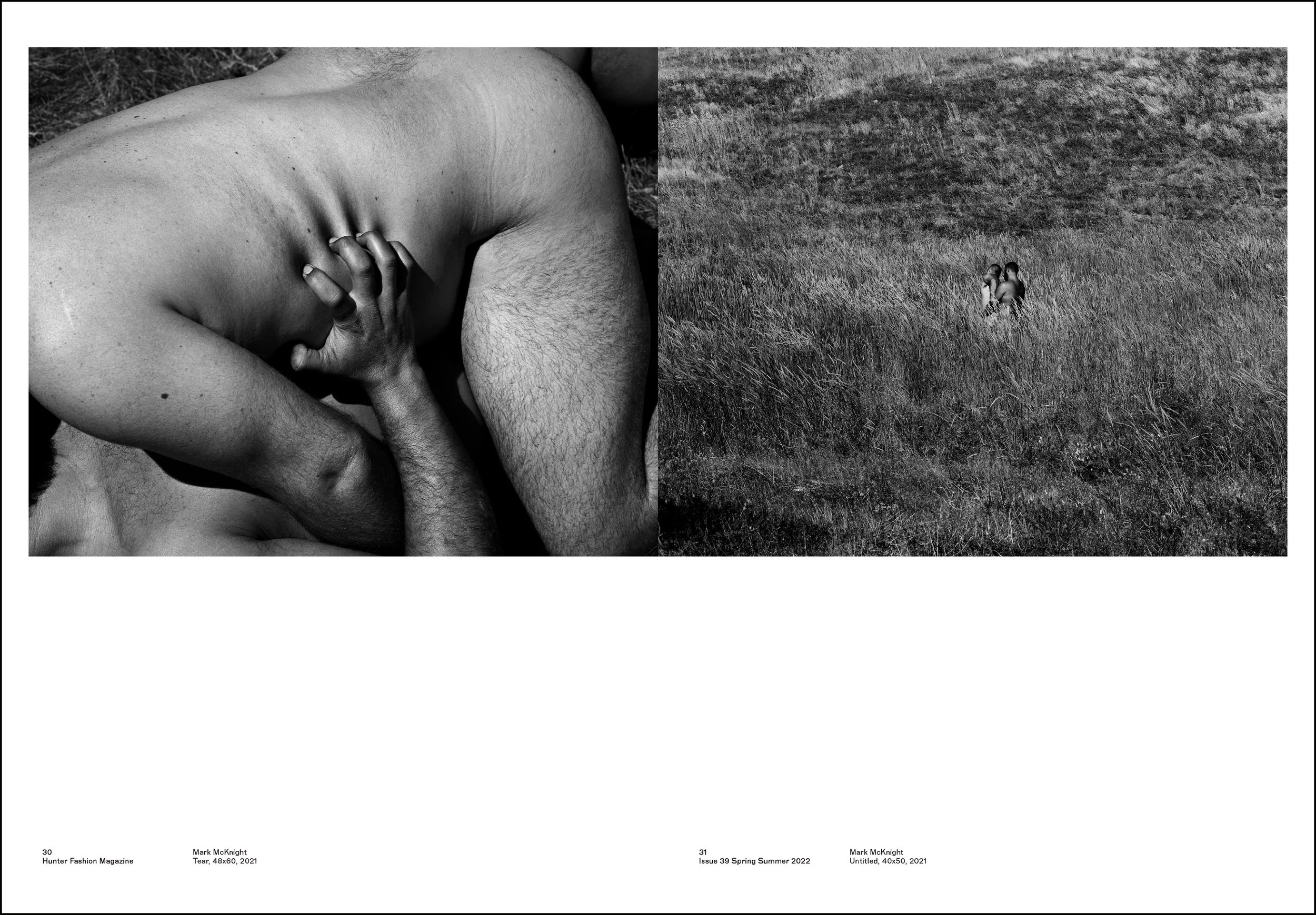

At the end of 2020 I published my first monograph, Heaven is a Prison, which describes the landscape of my native Southern California and two of my close friends copulating within it. The process of making that work was strange because it bordered on voyeurism. I was under the dark cloth observing and recording my friends through a view camera as they had sex. I felt paradoxically alone under the hood but also very present as an active participant – giving commands, moving body parts, introducing props. By the end of making the pictures they had jokingly christened me with the title “master daddy” because of the tone and attitude I adopted throughout all of these shoots. I guess I was assertive! Perhaps it’s a kind of consensual voyeurship? I should note that the book belies the consensual nature of the exchange. It feels very voyeuristic – something that is emphasized through the book’s design. It comes wrapped in an image of a cloud that has to be ripped open in order to access the contents. In other words, you have to defile this otherwise pristine, fetishized object… It’s a gesture that makes one complicit in the act of my voyeurship. If you made the decision to tear the cloud and open the book, you have asserted your agency and desire as a viewer. There’s no feigning passivity.

PMS: I am thinking about that with the Darkroom Mirror pictures because they enclose within them a closed circuit both voyeurism and exhibitionism. The viewer of the image at it’s making is the subject of the photograph. The external viewer in a sense doesn’t even factor, yet the awareness of that future presence is necessarily a factor within that closed space. The viewer is looking at the surface of a mirror. A mirror should include that viewer as part of the formal composition but the circuit having been closed ends up excluding that viewer, and you’re left with that aperture at the center of the photographing camera as the only way in or out.

SN: When thinking about debunking social constructs of what’s “real” regarding gender identity and the trans-ness of the photographs themselves as they are constantly shifting and becoming – I wonder how you are thinking about queerness and sexual identity through the material and the communal making of the work – how they are these components of external imposed structures in constant conversation with your own subjectivities? And how do they come to life within the frame of the photograph itself and the framing of the viewer?

PMS: Queerness for me is the place from which the social world emerges and how relating to the images through recognition and formal structures gets built. It’s not tied to any attempt at defining identity. Inclusion in the work does not define a subject’s gender or sexual identity. Presentation is not definition. Inclusion is not definition. They are about movement, and our mutual relationships. I’m actually most interested in positioning the viewer in either a privileged position of recognition, or negotiating being on the outside.

MM: I don’t feel like I have a license to talk about trans-ness, but I do have a license to talk about what it means to feel like I am constantly on the precipice of becoming another thing (or a truer version of myself). It’s probably quite clear at this point that I am a lover of double-meanings: I like queer as an inclusive term for describing a broader community to which I belong. I also like the word queer in its original meaning: “strange.” I move through the world with a fundamental understanding that all things are fluid; not just sexually but also subjectively and existentially – on a cellular level, who I am today is not who I was 10 years ago. That I don’t feel obligated to put boundaries around or define everything in my life feels like an unconventional (queer-as-in-strange) position to take that is the undeniable result of my social and sexual (queer-as-in-community) identity. Both kinds of queer apply. They are inextricably linked for me. The work I am making is the result of my subjectivity, not an illustration of it.

SN: I’m thinking of historical paintings of femme subjects and young boys dis-robing and dis-figurations as I look at your works — can you talk about the relationship to painting in your work, if it is there at all? As well as how it relates to gender and sexuality historically at the present moment?

MM: Art historically, I like looking at the use of hands. Michelangelo’s hands are a favorite – they look simultaneously strong and delicate which feels so queer. Similarly, I often pair corpulent queer bodies (that appear both powerful in their rotundness and graceful in their curvaceous softness) with sharp, “masculine” construction material. I think this signals queerness in some way. I want to be clear: my raison d’être is not combatting an oppressive art history. However, I’m excited about the prospect of my work inadvertently pushing back against a Euro-centric cultural standard for beauty or carving out space for the representation of other subjectivities, including my own. Above almost everything, I want to make images of the kinds of bodies I find erotic and I want to represent them so well that the beauty of these bodies and sexualities is irrefutable.

PMS: I think about Manet’s Olympia, the maid, her bouquet of flowers and then that curtain. Of the possibilities and erotic potential of being unseen but depended upon. Of being the hand that positions and controls, closes and pulls back the curtain. Of transforming what at first is marginalization into a queer power. And Olympia need never know. So the constant reference to painting is what photography inherited in staging by means of that curtain. A painter friend once mentioned to me that drapery was the showiest and easiest way to make something satisfying for the viewer. Maybe I got wrong what she was telling me, but it stuck with me.

SN: This is a multipart question that I am excited to hear what you think. Recalling Muñoz: “Disidentifications is meant to offer a lens to elucidate minoritarian politics that is not monocausal or monothematic, one that is calibrated to discern a multiplicity of interlocking identity components and the ways in which they affect the social.” I’ve always been very curious about the idea of fragmentation in both your works – it’s closely related to cinematic cuts – Can you speak to the relationship between the different materiality within each work, their transitions (sometimes sharp cuts, sometimes melting into one another’s body parts, or decapitated by other materials in the images) in relation to disidentity? How do you decide when the view has to shift to something else in the image? Does this happen through looking, sketching, performative actions in the studio or in environments?

PMS: Again, I’m not concerned with identity, but about recognition and how intimacy is actually the medium through which recognition works in terms of fragmentation. The fragmentation comes from play, experimentation, intuition that is informed by the real and ongoing conversations, friendships, relationships. It’s about editing. But yes fragmentation cannot be disengaged from metaphors of politics and identification / disidentification. So for me, I return it to the hand. My hand that cuts and arranges, tears or tapes, holds the material together. In that way it returns to my hand and desire.

MM: I crop images for a variety of reasons: at times it has to do with my desire to create a kind of claustrophobia within the image and upend a viewers understanding of what is being depicted (so that they might see something familiar anew). I’m not figuratively dismembering or decapitating anyone! I often use cropping to obscure the identities of the subjects so that the photographs can function two-fold: as a discrete record of my community and interpersonal relationships and as archetypal images that transform these men into armatures for larger concepts of desire, intimacy, vulnerability, and loss.

SN: When thinking of data collection and image readibility (especially of queer and minoritarian subjects) I want to ask how you see your process of arranging images that dis-allow for recognition of certain subjects – I see the technique of cutting and obscuring faces in your photographs as magical moments of protecting and caring towards the readability of queer and marginalzied subjects – in a way that their subjectivity is not being captured by “the system” somehow. Can you speak to this?

MM: I’m much more interested in a read of these men as archetypes. It’s not about anonymity. Regardless, both anonymity and archetype are forms of abstraction — a read of the work that also feels important. Much of my undergraduate education was spent studying New Topographics, in part because there seemed to be a resurgence in this mode of picture-making at the time, but also because of the people I was studying with.

As much as I loved my undergraduate education and aspects of New Topographics, the strategies many of those photographers were employing and the resulting conversation didn’t entirely resonate. The ways in which white, cis-hetero male subjectivity routinely get described as “objective” “pure”, and thus become an approximation of “truth” felt somewhat oppressive. Whose truth? And to the detriment of every other perspective? I don’t believe in “the photographic document” and I don’t believe emotionless banality is equivalent to photographic fact. I think my desire to photographically describe in a way that feels simultaneously “direct” but that also refuses so much (via posture and quality of print) speaks to this love-hate relationship I have with certain histories of photography, not to mention their aesthetic influence on my practice. Daddy issues! To your point — I certainly feel like I’m protecting myself, subjects, and our intimacies, but I’m also making photographs that I hope solicit speculation and empathy while also pointing towards the inherent limitations of the medium. I privilege the suggestive, poetic potential of photography even if the individual images appear affectless.

PS: I am also fascinated by that aspect and potential of both Mark’s work and mine, and how in the fragmentation they sometimes slip past censorship. I was absolutely thrilled when the NY Times printed a work of mine prominently but somehow discreetly depicting my friend’s scrotum on the front page of the arts page. I’m just having fun with it. I am honestly not making work to engage ideas of surveillance, tracking and those technologies. I am making work from a position of pleasure.

SN: Can you talk about the process of making work with friends? How do you organize images with other subjects in the frame, is it a collaborative process, do you decide together what the image composition is?

PS: It’s all about playing and having a good time. There are several formal starting points, built off of test works I have made by myself in the studio, or building off of successful photographs made with others. But we go from there.

MM: I hope those friends who “model” for me don’t read Paul’s answer! Often, my shoots are kind of arduous. People hold awkward or even painful positions, carry burdensome objects, or are penetrating each other often for hours in the freezing cold Pacific Ocean or in 100+ degree heat of the desert while I refocus my view camera. Sometimes I think this labor and dynamic is important to the work. I’ve been lucky that my friends believe in what I’m doing and are willing to sacrifice comfort, time and body to my creative practice! Shooting is somewhat improvisational. I often go in with an idea, but it’s rarely the picture that I end up choosing.

SN: How do you feel about your images entering and becoming part of historical queer archives and what they may mean to future queer artists 30 years from now? How do you imagine the conversation of visibility, value, validity, and representation changing because of the labor you are both putting in now?

MM: I don’t think that way about my work although I’m flattered by the suggestion that anything I’m making will be important to anyone that far in the future. As much as I love being a part of my community and a broader conversation within it, I hope that culture has evolved in a way that future generations of queer artists can make work without being exclusively identified as such. I find the dialog around work by queer artists (and artists by members of similarly marginalized groups) can sometimes be reductive, at times limiting their reception to an audience concerned almost entirely with restrictive identity-based frameworks. I actually can’t think of anything more un-queer. The more lenses through which to look, the better. Let’s complicate and confuse things.

PMS: I agree with Mark.

SN: What are you working on now? What’s next?

PMS: I’m trying to balance exhibitions and deadlines with teaching and faculty work, and somehow find time to rest, experiment and make new work. My second exhibition with Vielmetter Los Angeles opens this Fall and so I am in the midst of finishing and editing down a lot of new work for that. Since last summer I have been shooting at night for the first time, making works with long exposure in dark room lighting, and it’s been an exciting process seeing the resulting pieces. I am also deep in a publication project slated to arrive Spring 2023. It is a large experimental monograph that has been in the works for the past four years and finally last year got the ball rolling with the publisher and design, research and writing collaborators. It’s daunting, and a bit scary, and I hope the vision I have will succeed.

MM: At the moment, I'm finishing work on "Kiss of the Sun," my first European solo presentation. It opens at Kendall Koppe in Glasgow at the end of April. I'm also working on my first public artwork (an architectural project!), a 16mm film, a curatorial project that opens at Vielmetter in LA later this year, and a solo presentation at Mendes Wood DM in Sao Paolo that opens in Winter 2023.

Silvi Naçi is an artist and writer working between Albania and Los Angeles. Their interest lies in the subtle and violent ways that decolonization and migration affect and reshape people, language, gender identity, and social and cultural dynamics.